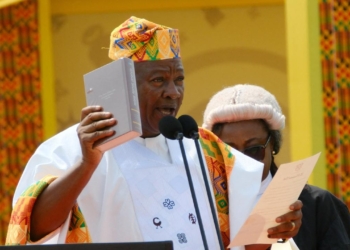

Dr. Mahamudu Bawumia is the vice presidential candidate of the NPP in the upcoming December 7 elections. It is not in the nature of presidential contests for a party or campaign to aim a significant portion of its attacks and propaganda at the vice presidential candidate of its main rivals.

Of course, being an integral part of a presidential ticket, a VP candidate is fair game in a hotly contested presidential election. The point here, though, is one of proportion. Why has the NPP’s Bawumia become such a thorn in the flesh of the NDC and a focal point of rival attack and attention in this year’s contest for the presidency?

It could be argued that rival party attacks on Bawumia are merely a reaction to Bawumia’s own very assertive and visible role in the NPP campaign. There is some truth to that. The latitude and visibility the NPP’s presidential candidate Nana Akufo Addo has trusted to his running mate is almost unprecedented in our modern presidential politics.

When John Mahama was first paired with the late Professor Atta Mills on the NDC’s presidential ticket for the 2008 elections, the NDC broke new ground in the individual prominence and visibility it accorded the then more energetic Mahama. Some believe that raising the profile of the vice presidential candidate was tactically necessary on account of Atta Mills’ widely suspected ill-health at the time.

In the current election campaign, however, the NDC’s presidential campaign billboards and ads prominently project Mahama but rarely feature his running mate. In contrast, the NPP’s presidential campaign billboards and posters routinely feature the Akufo Addo/Bawumia duo. The Akufo Addo/Bawumia ticket projects an exceptional chemistry, partnership, and mutual respect between the two.

More substantively, Bawumia has been the NPP campaign’s leading voice on the economy, economic policy, and public finance and has also led the charge against the project-related corruption and cronyism in the Mahama administration. In short, Bawumia could be said to have invited the barrage of negative attacks he has received from the NDC on account of the exceptionally high profile he has assumed in the NPP presidential campaign.

Curiously, though, the rival attacks on the NPP’s Bawumia have not focused on his suitability or qualification for the high office he seeks. In fact, the attacks have not even focused mainly on his claims and message in the areas of the economy and economic management, many of which have gone unanswered. Rather unusually, the aspect of Bawumia’s candidacy that has earned him the ire and disproportionate attention of the NDC is his ethno-regional identity–his identity as a “Northerner”.

Mahama and his surrogates in the ruling NDC have suggested to voters, especially in the Northern half of the country, that, as a Northerner, Bawumia is in the wrong party; that he has no future in the NPP except as second fiddle to the flagbearer; that there is even something inauthentic about his Northerner identity. The CPP flagbearer has added that Bawumia is an “Accra Northerner”.

Why are the NPP’s rivals fixated on Bawumia’s identity as a Northerner–and in a clearly disapproving way? What is it about Bawumia’s ethno-regional identity that unsettles especially the NDC?

This, of course, is not the first time the NPP has picked a demographically balanced ticket, with a Southerner/Akan at the top of the ticket and a Northerner as running mate. Before Bawumia there was the late Alhaji Aliu Mahama, who served as VP under Kufuor but failed to secure the party’s presidential nomination in the internal contest to succeed Kufuor. Bawumia himself is not new in the No. 2 spot. This is his third run as VP nominee of the NPP’s flagbearer Nana Akufo Addo.

In 2008, when he made his maiden run, Bawumia’s selection as running mate by Nana Akufo Addo stirred disapproval more within the NPP than without. Not only was the technocrat Bawumia new to party politics, his more seasoned rivals in the NPP also made much of the fact that he was new to the NPP itself, having had no previously known connection or affiliation to the party.

His subsequent retention as Nana Akufo Addo’s running mate in 2012 was still internally controversial, though not as contested or unexpected as in 2008. Bawumia, however, secured his place in the party more firmly after the 2012 election, when his highly visible and forceful role in the ensuing presidential election petition litigation caught the attention of many Ghanaians and made him a hero to the NPP’s supporter base, including some who may have previously questioned his bona fides in the party. Although the NPP lost the petition, Bawumia emerged from it with his national political structure substantially enhanced.

In the current campaign, Bawumia’s unprecedented visibility in the NPP campaign, his strong command of issues, as well as his cross-party appeal and likeability have cemented his status as a star politician both in the NPP and on the national political scene more broadly. Added to his relative youth, this makes Bawumia the politician to watch–not only within the NPP, but also (and more importantly) from the perspective of the NDC. The reason is not hard to fathom.

The NDC has self-consciously positioned itself within the Ghanaian political terrain as the “non-Akan” party, tapping into a strain of historical and emotive suspicions, prejudices, antagonisms, and grievances, both real and imagined, held against “Akans” (but especially Asantes) by a number of ethnic minorities. To these groups, the NDC has presented itself as their natural political home.

As part of its electoral strategy and to give clearer definition to its identity-based coalition, the NDC has also worked hard to define and tag its main rival, the NPP, as an “Akan party” and, thus, not a political home for non-Akans like Northerners, Ewes, and Ga-Dangbes.

Within the Akan family, the NDC’s identity politics takes on a slightly different, yet still politically significant, twist: No longer is the NPP just an “Akan” party, it is portrayed as an Asante/”Twi” party, which again taps into residual resentment mainly of Asantes among certain Akans, some of it dating back to precolonial rivalries.

The obvious political aim of playing up intra-Akan differences is to make the NPP also unappealing to significant sections of non-Twi Akans, notably Fantes and other Akans in the Central and Western Regions of Ghana. Peeling off significant sections of Akan voters enables the NDC to construct an identity-based coalition that is at once nationally representative in appearance and formidable as an election machine.

In this year’s election campaign, the NDC’s identity-based “us versus them” electoral strategy and politicking have been strongly and overtly on display, especially when Mahama and his surrogates and party leaders campaign before non-Akan audiences in the three northern regions and the Volta Region. That this strategy has been perversely effective and politically beneficial to the NDC cannot be disputed.

A widely perceived ethnic chauvinism and immodesty on the part of Asantes in the assertion and projection of their culture, history, and identity in relation to others is a stereotype or sentiment that is easily mobilized and exploited politically to underwrite the NDC’s identity politics and propaganda. But the primary litmus test applied by the NDC to validate its Akan/non-Akan logic is the issue of the ethno-regional identity of a party’s presidential candidate.

The NDC points to the fact that, while it has fielded Ewe (Rawlings), Fante (Mills), and Gonja/Northerner (Mahama) presidential candidates since 1992, the NPP has fielded only Twi-speaking Akans (Adu Boahen, Kufuor, and Nana Akufo-Addo). (Interestingly, the NDC, too, has yet to field a Twi Akan even as vice presidential candidate) On its part, the NPP responds that, unlike the NDC, its internal contests to select a presidential candidate have always been open and nonexclusive and their outcomes have not been predetermined or engineered by party elites (like Rawlings’ in 1992 or Mills’ in 2000 and 2004) or accidental (like Mahama’s in 2012).

However factually correct or legitimate the NPP’s explanation, the political resonance of the NDC’s litmus test is hard to dismiss. Bawumia’s political ascendancy in the NPP, however, threatens this strategy and propaganda of the NDC in both the short and long term.

The NDC’s elites and strategists must know that, given Bawumia’s centrality in the current 2016 campaign and his national likeability and appeal, victory for the NPP in the December 7 polls will instantly propel Bawumia to front-runner status within a post-Akufo Addo NPP. Anticipating this prospect, the NDC has made much of the fact that, as vice president to Kufuor, Aliu Mahama, also a Northerner, failed to secure the NPP’s nomination for a flagbearer-successor to Kufuor.

This fact, however, is not a precedent of much relevance or applicability to Bawumia. As a politician, and despite his relative youth in Ghanaian politics, Bawumia has earned, in his own right, a standing and following both in the NPP and nationally that goes far beyond any that the late Aliu Mahama could garner.

Therefore, unlike Aliu Mahama, Bawumia’s emergence as front-runner, in the event of a 2016 NPP victory, will make him the man to beat and, thus, the most likely choice of the NPP as flagbearer in the immediate post-Akufo Addo era.

While a Vice President Bawumia could still face competition within the NPP for the party’s flagbearship post-Akufo Addo, a rejection of a Vice President Bawumia as the party’s presidential candidate is not only highly unlikely on account of his incomparably strong political standing, but, more importantly, such an unlikely result, were it to happen, would deal a mortal blow to the NPP’s ability to escape its Akan-exclusive tag and damage the party electorally.

In short, the logical effect of an NPP victory in the December 7, 2016 polls will be to put Dr. Bawumia on course to claiming the party’s flagbearership after Nana Akufo Addo’s term ends. Such a development would instantly undercut a central pillar on which the NDC’s identity-based electoral strategy and coalition has been constructed; namely, the notion that the NPP is an Akan-exclusive party and, thus, not a political home for Northerners or other non-Akans. If the NPP can no longer be smeared as an Akan-exclusive party, then a basic thrust of the NDC’s raison d’etre begins to fall apart, with major implications for the future viability of identity politics in Ghana.

It is indeed in the long-term interest of the NDC to perpetuate the Akan/non-Akan, Twi/non-Twi division as the primary basis for political party preference and politicking in Ghana. Conversely, the NPP’s long-term electoral viability is not served by the entrenchment of identity politics along an Akan/non-Akan axis. This is why victory for the Akufo-Addo/Bawumia ticket in December 2016 elections represents a mortal threat to the NDC and a unique opportunity for the NPP.

If, however, the Akufo Addo/Bawumia ticket were to suffer defeat in the December polls, that outcome would dim, though not extinguish entirely, the prospects of Bawumia as likely flagbearer of the NPP in the immediate post-Akufo Addo era. If the Akufo Addo/Bawumia ticket fails to win in December, Bawumia may no longer be owed the automatic frontrunner spot and deference within the NPP that a victory would surely guarantee him.

Other presidential aspirants in the NPP may then feel compelled to contest him and justified to question his ability to expand the party’s demographic base of support beyond its Akan strongholds. And that precisely is the outcome the NDC would like to see. That is why the NDC is going to extreme lengths to undercut the political appeal of the Akufo Addo/Bawumia ticket among non-Akan voters.

The NDC’s concern, however, extends beyond the immediate impact of losing the 2016 election. The greater worry is that the success of the Akufo Addo/Bawumia ticket will set in motion a political dynamic that will almost certainly produce a Bawumia at the top of the NPP presidential ticket and thereby weaken significantly the efficacy and viability of the “us versus them” identity politics that has become a central tenet of the NDC way of politics.

Given the risks to social peace and cohesion associated with stoking tribal fires and playing the tribal game for partisan gain, as well as its tendency to impoverish the quality of our democracy and governance, a weakening of the political salience of the Akan/non-Akan logic should be salutary for the progress of Ghana. This may take more than one election cycle, but it would be a positive first step.

It is, of course, possible that, should the Akan/non-Akan division lose a significant bit of its political bite, the NDC might awaken and invigorate another politically salient identity like religion. But the political cost of using, say, religion as an electoral wedge issue if the Muslim Bawumia were to emerge as the NPP’s flagbearer would be too prohibitive for the NDC itself. Perhaps class would become the new “tribe”.

As it is the more populist of the two main parties, the NDC could turn to “class” and, thus, gravitate more towards a class-based ideological politics, in which the NPP is presented as the “elitist” party. There is already some of that going on, and it is sometimes mixed in with ethnicity. However, if class, rather than ethno-regional identity, became the primary basis of political differentiation between the NPP and NDC, electoral outcomes would not necessarily favour the more populist NDC, given the fact that the NPP, despite its self-image as the party of business, has a strong record in the area of economic justice and pro-poor policies.

In any case, a shift away from ethnicity in favour of class as a primary basis of party politics in Ghana would be a most desirable outcome. For one thing, it would bring us closer to “issues-based” politics than currently obtains and also reduce the threats to social cohesion associated with crude identity politics. Unlike ethno-regional identity which is generally unalterable and thus easier to exploit in an “us versus them” manner, class status is fluid and aspirations of class mobility are strong even among poorer segments of the population.

Thus, beyond the possibility of moving us past the toxic Akan/non-Akan identity politics, an Akufo Addo/Bawumia victory on December 7 and, for that matter, an all but certain Bawumia leadership of the NPP presidential ticket in the near term, holds the best promise yet of ushering us into a new kind of politics, one in which “kenkey and fish” issues and other developmental concerns define and drive the content of our politics and governance. A weakening of the political use and attractiveness of identity politics might also open up space for a third party to thrive.

For all of these reasons, the Bawumia factor is an extraordinarily critical piece of the 2016 December 7 elections. The electoral fate of the Akufo Addo/Bawumia ticket will go a long way toward shaping the character of politics and governance in Ghana. Importantly, it will have a strong influence on whether we break free from the counter-developmental and destructive Akan/non-Akan identity politics that only serves the interests of a small class of political entrepreneurs and party elites or remain mired in it for the foreseeable future to our collective detriment.

It is indeed an irony that Dr. Bawumia, whose choice as NPP’s presidential running-mate seemed bewildering to most when it was announced eight years ago, has become today arguably the most significant driver of change in Ghanaian electoral politics. He may well represent, in course of time, Nana Akufo Addo’s most enduring gift and unifying legacy to party politics and democracy in Ghana.